Quadropolis Review

on May 17, 2016

If you think Quadropolis is nothing special, I don’t blame you. It is one of those games where each player has their own board and everyone is largely doing their own thing. At the end you are left with a nice little city and a score attached to it. But if you persist the depth rises above the simplicity, and Quadropolis reveals itself as a surprisingly deep game in the tradition of classic German designs. If this were the late 1990s or early 2000s I wouldn’t have been at all surprised to see a design like this packaged as part of Alea’s classic Big Box line, the series that produced such classics as Taj Mahal and Puerto Rico. It’s not as impactful as either of those games, but what Quadropolis foregoes in originality it makes up for in reliability. This is a very flexible design that allows the player considerable freedom to pursue several different strategies and slip between them as needed.

To some extent Quadropolis is what has been termed a “walled garden†design. The players each have their own player board and they will be working on a city that will be all their own. The interaction all happens on the center board, where over several rounds players will take turns selecting different buildings to add to their city. All of these structures will score points in different ways depending on what they are and where you place them. Some buildings, like residential areas or some ports, will bring in new inhabitants. Others, like power plants, will produce energy. Every building, no matter the type, will require either inhabitants or energy to score points at the end of the game, so as the game goes on players must balance their scoring strategy with the needs of their city. It’s tempting to go for that fifth public building, but then you really need that power plant to generate energy for your shops.

Those looking for an intense narrative experience had best look elsewhere. This is a game for people who want to build things. It is also one that allows a surprising amount of freedom for such a straightforward game. All of the interaction comes on the center board. Each player has access to numbered architects, and these are used to select buildings by placing one on the side of the board, counting into the row or column to which the architect points and taking the one that matches the number on the architect. Once an architect is in place no one else can use the space, and the tile they just selected is replaced by the urbanist, a big pawn who further limits what the next player can pick. While these constraints can be a nuisance, plans are usually rerouted rather than totally thwarted. If you can’t get the precise tile you want you probably have other good options. From one perspective this can be considered the bare minimum of interaction, but the overall effect is a pleasant game that allows the player to explore different strategies without too much hassle from other players.

When players begin to explore these strategies the game really opens up. You probably can’t do everything well, but you can find a couple of buildings that will feed off of each other and focus on those. But then there are occassions when you can’t find anything that applies to your main strategy, and you get a building that then might open up some new strategies. When you begin to play with eyes on other player, you then start to consider grabbing things to mess with them, even if it doesn’t help you much. These are not qualities unique to Quadropolis, but this game does them so effortlessly and without too many rules that its appeal is amplified.

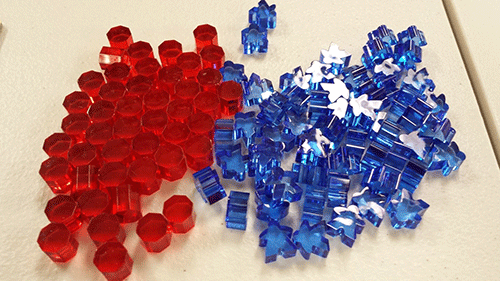

It helps that Days of Wonder has made a very attractive and approachable product. Many of their games utilize similar art styles, but this is one that feels largely distinct in their catalog with a high degree of usability, with lovely touches like the acrylic meeples and energy barrels. The only quibble could be the player mats, which are a heavy cardstock rather than cardboard, but it’s really not a big deal. In a surprisingly effective move, there are actually two play modes, Classic and Expert. The Expert mode ties the architects to a common pool, rather than giving each player a set of them. It also has a bigger board, an extra round, and a couple of extra buildings to play around with. I do prefer the expert mode, since it is a more strategically rewarding experience and requires the players to diversify a little more to do well. But the Classic mode is actually quite good as well. It’s a more approachable game, and it doesn’t sacrifice much in the way nuance to get there.

There are times when I miss the early games of Days of Wonder, like the slightly wilder experiences of Mystery of the Abbey and Pirate’s Cove or the more accessible worlds of Ticket to Ride or Small World. But like Five Tribes before it, Quadropolis shows how well Days of Wonder can do with a classical German-style family game design. It’s a polished game that will appeal to a lot of people, and it’s one I look forward to enjoying for a long time.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist