Path of Light & Shadow Review

on Jan 11, 2018

Critical Hits: Its combination of deck-building and area control is good, and hints at how it could be great. Excellent use of ruination in combat

Critical Misses: Narrow path to optimize your deck, which is a hallmark of deckbuilding, and clans’ morality isn’t reflected in whether or not they join you

Hybrid games are all the rage in this stage of board gaming’s evolution, and Indie Board and Card’s latest entry combines deck building with area control and just a dash of morality to create a unique empire builder for two to four players. Path of Light and Shadow’s mechanics work well together for the most part, and once players figure out how to make the game work for them, it delivers a fun, Scythe-like pseudo-kingdom experience.

Early games of Path feel somewhat random. Each player’s avatar journeys across the different realms to sort-of construct buildings and conquer lands, gathering followers from one of five different clans along the way to build their deck. I say sort of because unlike Scythe, building don’t appear on the map, but like Scythe, they don’t exist in any kind of “you could lose them†way. It’s really more of a tech tree than a series of construction projects, but serves the game’s purposes.

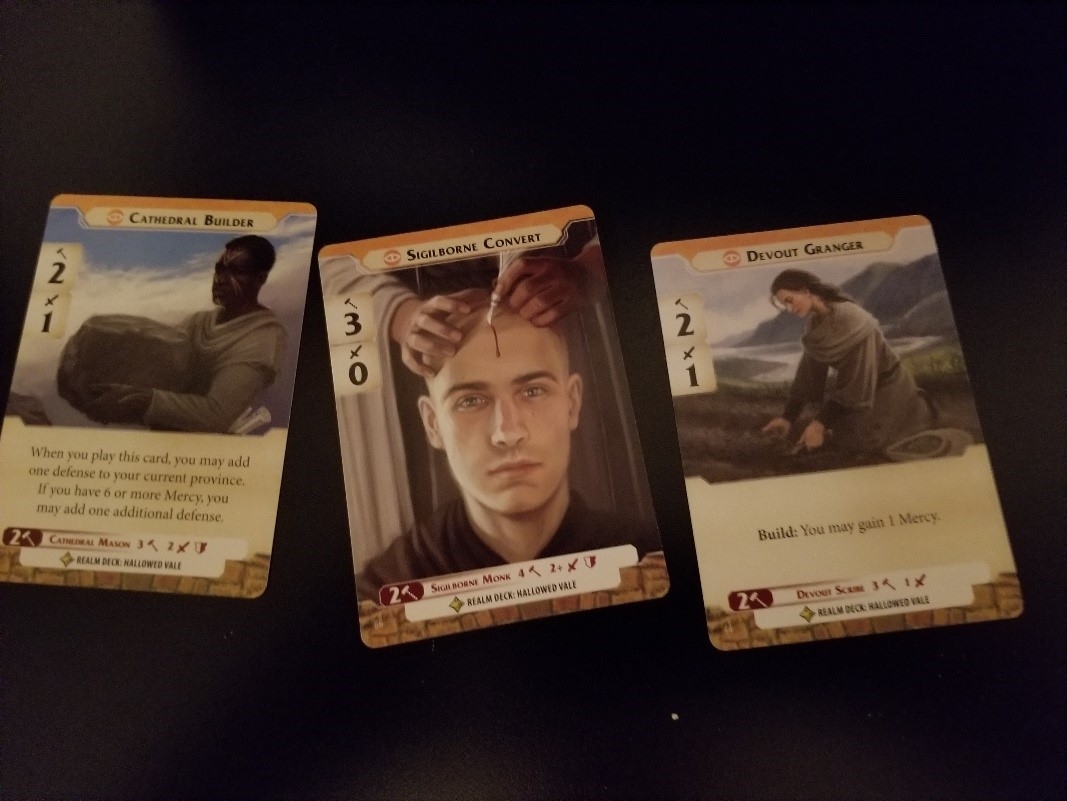

The path hinted at in the game’s title is one of either mercy or cruelty, and the different clans lean in different moral directions. It’s an interesting idea that helps to create a fantasy world, but the followers you collect depend solely on geography, so it’s possible to lead a horde of ravagers into a realm, ruin its castle during your conquest, and end up with a handful of peaceful monks joining your ranks after the battle’s done.

Perhaps “Feast on their entrails†is a euphemism, brothers

Players can tailor movements to increase the odds of getting desired recruits by restricting their travels to certain points on the map, but at best it’s a 50-50 shot with each realm deck, so the gathering of followers feels somewhat abstracted, or at least at odds with some strategies. This causes frustration with new players since the lion’s share of influence, the game’s victory points, depends on area control, so fighting for realms with other players can result in a hodge-podge of cards by the later stages in the game, defying the spirit of deckbuilding.

It’s not that I don’t need you. I just don’t need you alive

Once the board and cards become known to players, strategies form and games tighten up. Opponents choose the path of cruelty or mercy and play accordingly, conquering (and ruining) the board or building structures and promoting clan members to beautify the realm, and the game rewards each strategy if players maximize their path. Both paths to victory are viable, though early conquest seems a bit more so, but players wishing to stick to the middle ground will find the going getting tough as the game progresses, since few cards reward a neutral morality as much as they reward the extremes.

This moral path is an interesting one, and could have been spectacular with just a couple tweaks. Acquiring followers based on your location means people from ideologically opposed clans will join your deck, and it can be a struggle to figure out how to use them. Culling useless minions only favors one play style, so merciful leaders amass a pile of cards in the late game that make it difficult to cycle through and find your powerful upgraded followers, while cruel players routinely clean out the weak and consistently draw powerful warriors to fuel their conquest. A third path does exist, acquiring additional followers to gain mercy, then killing ones you don’t want to gain cruelty, hanging around the middle of the moral scale and foregoing the benefits of extreme followers while trying to walk either a construction or conquest path, but when Yoda and Mr. Miyagi are both against this philosophy, it should tell you something.

Try, and be squished like grape

Speaking of conquest, taking territories is one of the better features of the game. It combines deterministic unit values with some dice rolling for a nice mix of strategy and risk, adding ruination to further enhance the feel of a real world. The size of a territory’s castle determines its inherent defense (and scoring) value, and each attack has the chance to cause ruin, enabling easier conquest in the future, even if the attack is victorious. Ruin can be repaired, but followers with that skill are rare, and they lean toward the merciful end of the scale, so marauding players may sweep across the map, then find themselves ruling a broken junkyard by the end of the game.

This mechanic helps to balance out the two paths, since conquering realms yields more game-winning influence than building and promoting in general, but ruin is a function of die rolls, so there’s no guarantee your warmongering opponents will reap what they sow by game’s end. This isn’t to say the path of mercy is inferior; in many ways it may be the better of the two, since the merciful followers can rebuild ruined territories, yielding more victory points during scoring turns, but the scoring system does lend itself toward conquest. Players wishing to sit quietly, content to promote and build, may find themselves lagging behind their warlike counterparts.

Path of Light and Shadow combines disparate mechanics in a fresh way to deliver an empire builder with solid, consequential combat, thematic followers, and varying paths to victory. With a couple tweaks it’d be an amazing world to visit and would truly reflect the moral path players choose to walk, but as is it delivers a challenging hybrid that scales well for all player counts and provides an engaging tabletop experience.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist