John Company Review

on Mar 8, 2018

Critical Hits: Singular design concept; exceptionally strong historical themes; freewheeling negotiation

Critical Misses: Fragile and sometimes unforgiving

Just as the world has never again seen anything quite like the East India Company, there’s nothing quite like John Company, for better and for worse. At its height, the historical company raked its fingers over half the world’s trade, fielded a private army twice as large as that of the British Empire, and eventually frittered away its dominance on corruption, vainglory, and a crushing military overhead. If that doesn’t fit your notion of a good time, you might as well steer clear, because while John Company contains both cubes and economics, it’s anything but an economic cube-pusher.

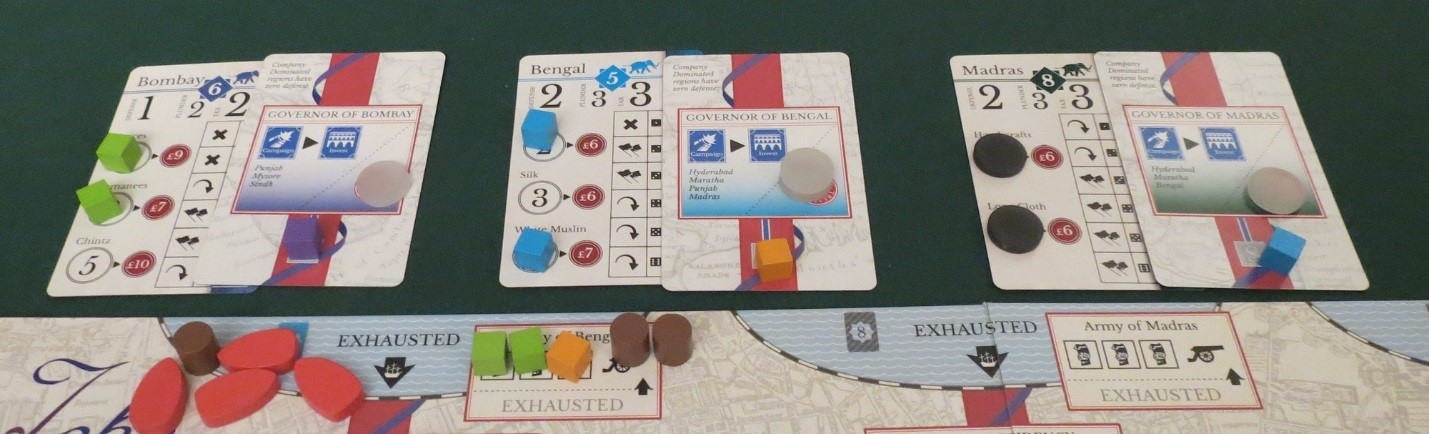

At its core, this is a negotiation game. Every player commands a well-to-do family of enterprising adventurers, captains, officers, and writers, all looking to climb the ranks of high society by first getting filthy rich — and filthy notorious, if that’s what it takes. Earning points is a multi-step process, requiring both a bursting wallet and retirement from one of the company’s senior offices, and while there are plenty of ways to hedge your bets, it’s rare that you’ll have full control over when that one nephew will decide he’s done being the governor of Bengal. Which is to say, your opportunities to score might arrive sporadically, all at once, or possibly even never, depending on where your family members wind up within the company and whether they get around to retiring.

In fact, company offices are one of the game’s principal bargaining chips. Every round — representing approximately fifteen years — any vacancies must be filled, from the simplest of tasks in ship purchasing and military affairs all the way up to the high and mighty chairman of the entire company. Whether filled by appointment or the greasy-fingered machinations of the court of directors, it isn’t uncommon to see players exchanging money, promises, or “promises,†the game’s loosely formal contracts that must either be earned back or incur a penalty later on, in order to secure the positions, ships, factory contracts, and even official support that they need to succeed.

This focus on negotiation reaches its fingers into nearly every aspect of the design, creating an aura of freewheeling greed that’s oppressive in its refusal to let up. Want to be promoted into a premium position? Be ready to shell out handsomely. Want extra trade goods or military support deployed to your presidential office in Bombay? Crud, would you prefer the director of trade to make a single common-good decision? Get ready to fight for it. The historical East India Company was infamous for how much of its proceeds were lost to corruption, and that’s also the case here.

If this makes John Company seem uncommonly stubborn, then just wait until I tell you about its fragility. In addition to the usual business of running a company and exploiting foreign nations, every round also sends the event elephant rampaging across India, sparking rebellions, attempted conquest, and economic swings. These are occasionally positive, but more often disastrous, especially if they befall a region under the company’s thumb. Then a single misstep in administration might result in burning trade fleets, the collapse of the local colonial government, or even the total ousting of the company from the region. Such misadventures might even be impossible to recover from.

Let’s recap. To be good at John Company, you’ve got to be a conniving git, possibly silver-tongued, capable of remaining patient with other silver-tongued gits, and perceptive of the situation on the ground in faraway India. With all that overhead, what’s to prevent the game from collapsing in on itself like a ballooned military budget?

For one thing, spurring the company into motion is an exercise in nudging a limb here and massaging a power broker’s wallet there, or perhaps securing a position of authority and using that office’s treasury to promote your long-term goals. Soldiers can campaign in faraway lands to bring home enormous quantities of plunder, then use those ill-gotten gains to secure governorships over the very lands they marched across. Sailors can become interloper captains and leech off the company’s profits to fill your family’s coffers. Shipyards and factories can provide crucial sources of income and political power. And, eventually, you can found your own firm and work directly against the company’s interests while also pursuing a career within it.

At every step, John Company evokes something that very few games even attempt. Its East India Company is a house divided: a promoter of stability in India, an exploiter of foreign resources, a stepping stone to respectability, a competitor to be buried, or an over-engorged cash teat ripe for the suckling. And rather than being one of these things at a time, it’s all of them all at once, sometimes even within your own family.

As such, the game quickly becomes less about promoting a single course of action and more about bulking up to pursue your goals while remaining flexible enough to duck and weave around any punches that get thrown your way. On one end of the company, you’ll be striving to retire an executive into a royal marriage, while downstairs you’re snapping up political capital to enact laws that will crush your opposition, and out in the wider world you’re operating a firm whose entire modus operandi is that they can fulfill orders of sailcloth and pearls to Hyderabad long before the East India Company gets up in the morning. It’s even possible to streak ahead into an early lead, then work to shatter the company from within in order to block anyone else from replicating the secret to your success.

Most importantly, this whole messy negotiated process is a wonder to behold in action. For every instance of aggravation, it provides four moments of bombastic success, far-reaching promotions, or subtle company coups. This comes at a cost, as it’s entirely possible to negotiate yourself right out of relevance, but it strikes me as appropriate that a game about the promises and perils of such dramatic endeavors should permit its players to fail.

The final result is one of the smartest and most exhilarating historical games ever crafted — especially for a game that’s not strictly about war — albeit one that I’m reluctant to recommend to anybody whose palate might not conform to the game’s brusque flavor. Still, although John Company is complicated, uncompromising, and sometimes fragile, it’s also a monumental achievement of historical verisimilitude.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist