Chariot Race Review

on Apr 18, 2017

Racing is one of the oldest sports; the first recorded Olympic event was a footrace won by a cook named Coroebus. As a contest, it just makes intuitive sense—the winner is the one who finishes first—so it's no surprise that the race format has endured and spread to encompass so many modes of locomotion. Racing games are nearly as old: the 5000-year-old Egyptian game Senet was a race, as are the Indian Pachisi and Gyan Chauper, which survive today as Parcheesi and Snakes & Ladders. While the finish line has been replaced by a VP track in many modern board games, the racing mechanic is still ubiquitous in mainstream and family games, and it's easy for a new design to get lost in the pack.

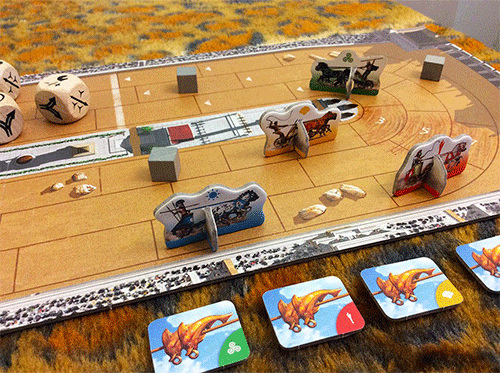

The cardboard chariots lend the game a lot of personality, but it's still essentially a peg game.

Forget what you think you know about Matt Leacock, designer of the quintessential co-op game, Pandemic. It's true that he's designed family-friendly games before, including Knit Wit, about which Raf wrote, "there is no grand strategy ... only a beautiful shared experience you stitch together across a table," and Forbidden Desert which Jason wrote "bridges the gap between ease of access and demanding narrative." I reviewed his first family game, Forbidden Island, with the line "you shouldn't mistake this simplicity for a dip in quality (or difficulty)." But believe me when I tell you that this is Leacock's simplest game yet, and the wheels are starting to come off.

This isn't Flamme Rouge, with its modular track and slipstreaming mechanism, nor is it Grand Prix, with its strategic, pack-driven movement. This is two laps around a circle with no cards or other components to distract from the primary objective: going really fast, but not so fast that your chariot falls apart. Each player gets a Chariot Board (really just thin cardstock) which tracks your vehicle's damage, speed and standing with Fortuna, goddess of fate. Your speed is equal to the spaces you must move each round, which starts out as four, but before moving, you also get to roll a handful of wooden dice. After one optional reroll, these dice might allow you to adjust your speed up or down, make lane changes, or attack the other racers with javelins and caltrops. Cornering at high speeds or being targeted by attacks damages your chariot, and if your durability ever drops below zero, you're out of the race.

When I think of Matt Leacock, I think of ingeniously elegant systems like Pandemic's "shuffle to the top" when an Epidemic is drawn or Roll Through the Ages' clever take on feeding your population. There are a few Leacockian twists here, too, the primary one being that most dice effects are non-optional. For each speed change you roll, you must adjust your chariot's speed up or down by one. Another die face that forces you to increase your speed by two plus take a point of damage as your horses become panicked. You really get the sense of being pulled along by creatures you can't fully control, creatures that are fairly well trained but could trample you to death in a moment of panic. Furthermore, as you increase in speed, you get fewer dice to roll, which equates to a loss of control. You can barrel along just fine in the straightaways, but if you want to slow down for a corner or switch lanes to avoid some rubble, you'll have to put your faith in Fortuna.

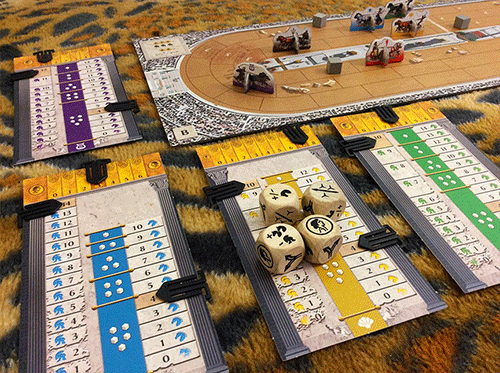

The alternate chariot boards have less impact than I'd like, but the rubble is a necessity.

Fate points are spent on dice manipulation or to repair your chariot, which becomes increasingly important as taking damage not only can knock you out of the race, but also resets your speed at the start of the round. Driving recklessly to get into the lead leaves you in a precarious situation if you can't afford the repairs. Of course, the game is made for driving recklessly, and it's normal for half the chariots to be knocked out before the race is over.

The game comes with a couple of variants. The B-side of each chariot board has a unique set of stats: some chariots have a higher top speed but can take less damage, others start with more or fewer Fate points, et cetera. This was less fun than it sounded. The B-side of the racetrack itself presents a more dangerous course with certain spaces occupied by piles of deadly rubble. Hitting one of these results in instant destruction, which means you'll need to budget your Fate points even more sparingly to ensure you can get a lane change when you need one. I found that this board layout resulted in a more exciting, densely packed game with more interaction between the charioteers, but it didn't play well with the variable chariot boards—the player starting with 0 Fate can be eliminated in the first round by a bad roll.

Chariot Race is as simple as racing games get. It needs that extra complexity from the rubble to create any tension or interesting decisions. Even then, the lack of track variety means this game probably has a shelf life. Despite some Leacockian cleverness, it's just another day at the races.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist