Amun-Re Review

on Apr 5, 2017

In 2003, Reiner Knizia released what many regard to be his last "gamer's game", although what a "gamer's game" actually is, whether or not Dr. Knizia ever actually designed those, and whether or not Amun-Re is the last of them that he may or may not have done is all up for debate. What is clear is that this is one of his more complex, intricately designed games and that it is, like all of his best designs, rich with theme and compelling gameplay. The old Hans im Gluck/Rio Grande printing of the game has been out of print for years, but the new Tasty Minstrel edition is one of those good reprints where they didn't mess with success and really only updated the product values.

That said, I find myself still preferring the original, if only because it had these lovely little resin bidding stones and pyramids. It's also not quite as sleek and clean looking as the original, which is kind of a disappointment. Issues of personal taste aside, the new edition is totally fine, so don't let me scare you away from it on that count. We've had some really great Knizia reprints recently, such as Ra, Medici, Tigris and Euphrates and Samurai and this release is definitely up to those high standards in terms of visuals and material quality.

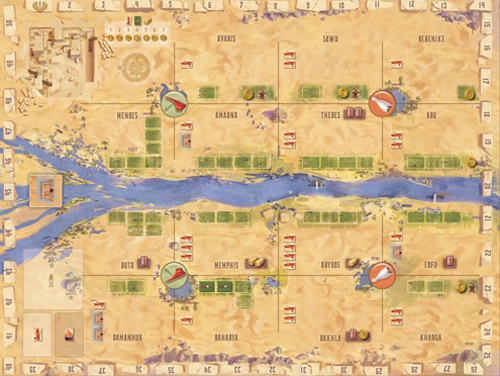

A board gamer's eye view of the Nile delta.

As for the game itself, it's interesting to note that it was met with somewhat mixed reactions when it released. I recall there being a sense of disappointment and redundancy, and even I had mixed feelings about it for a while. I think it could be because this is one of Dr. Knizia's less immediate games, it isn't as acutely arresting as Tigris and Euphrates or Ra is. You don't have that moment where halfway through you get how devastatingly smart it all is. Instead, you might get that feeling five games later.

As for the redundancy, by 2003 Knizia was known for auction games (especially after the killer triumvirate of Ra, Medici and Modern Art) so it was kind of a from-the-hip assessment that this was just another one of those. It's really an area control and development game, quite unlike anything else in the Knizia canon, but it does have an auction game sort of riding on top of it all. One thing that Kniziaphiles relish is how the designer will refine and reiterate core mechanics, gameplay concepts, and processes. So you might see later titles evidence a sense of evolution and development. Amun-Re has some of that, sure, but it is also interesting something of a unique game in his ludography. It's hard to say whether it is a culmination of past ideas, an endpoint, or an apotheosis if only because it is such a different game than Knizia is and was known for.

It's ancient Egypt, obviously, and players represent royal families competing to accrue wealth in terms of provinces, farmlands, temples, and of course those monumental mortuaries we call pyramids. The game takes place in two distinct ages of three rounds each, creating an interesting split between the first and second halves of the game. But more on that later.

Each round has four phases beginning with an auction for randomly drawn provinces. These cards indicate territories that lie on either side of the Nile River that runs across the board and they may be in either downstream or upstream provinces, on the banks of the river or further inland. Each also has varying numbers of fields for farmers, pyramids, and other developments. Further, some territories impart bonuses such as a gold mine, caravans, temples or the favor of the gods. To place a bid, you put a scribe (formerly a stone) on a gold value on one of the cards. The next player can choose to overbid you, and if that happens you must immediately place your scribe on another province card unless you have a special Bribery favor card. The bids continue until there is no province under contest, at which point players claim the cards and mark them as their own on the board.

What follows then is a Market Phase, where players buy farmers to work the land, favor cards to achieve special advantages, and stones to build pyramids in their lands. Costs are on an escalating scale and you buy in a specified order, so you've got to plan accordingly. If you put three stones in a province, it makes a pyramid and that is obviously a good thing.

The third phase finds players making an offering to Amun-Re, which is a sort of blind bid, one shot auction to see who offers the most. Everyone must play a gold card or their Theft card, which means they steal 3 gold from the collection plate. Whoever bids the most gets to take three items (favor cards, farmers, stones) and the start player token for the next round with the second place player getting two items. Thieves get nothing, obviously. What this bid also does is to set the scoring values for temples and the amount of gold that farmers and caravans will produce. The more generous you are to Amun-Re, the more he rewards you with prosperity.

All the cops in the donut shop (way oh way oh) are not included.

Finally, the Harvest phase closes out the round with payouts for gold mines, caravans and farmers. This is how the income is generated with the mines offering a flat rate with the others conditional on the offering. Developing a viable economy and keeping Amun-Re happy is crucial to having enough money to win the province bids in the subsequent round and having enough gold left over to develop your holdings.

All of this is scored twice. Once during an intermediary scoring representing the close of the old age, after which everything except the pyramids and pyramid stones is washed away and province ownership is completely reset. The pyramids are, in fact, the only permanent legacy of your earliest struggles. This is a beautifully simple thematic touch. At the end of the second age, there is a final scoring. Values are assessed across a couple of vectors- you get points for temples, pyramids, having a province with the most pyramids on either side of the Nile, and favor cards.

This mid-game split is such a brilliant piece of design. It doesn't just completely wipe the board, it also changes the valuation of the provinces based on what players had previously done there. So pyramids add lasting value...while nothing else does. This is such a neat touch, and it interesting to watch in action how you may lose your best province and wind up fighting to regain it- and your family's dynastic lands, effectively- in the second age.

This is a rich, masterfully designed game that is as satisfying as it is fun to play. It does not lack for player interaction and it tells a vibrant story about the rise and fall of Egyptian dynasties. The goal is, really, to build something that will last while you are struggling for more ephemeral things like income and religious favor. It's an interesting dichotomy between what matters in the end and what doesn't, and that is what Amun-Re's theme is illustrating. This is a reprint of a game that any serious fan of Knizia simply cannot miss, and those designing Eurogames-style titles today would do well to look at how this game incorporates unique mechanics, a meaningful theme and player interaction into its strategic gameplay.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist