A Feast for Odin Review

on Oct 26, 2016

Back in the mid-1990s, when German games were starting to change the hobby here in the US, Uwe Rosenberg was known chiefly for one game- the timeless classic Bohnanza. It’s a super simple, highly interactive trading and negotiating game with just a few rules governing the outrageous bartering, begging, cajoling and brokering that goes on in it. Years on, Agricola happened. That was a great game too, highly thematic and detailed with tons of options and possibilities for strategic play. Now, every Rosenberg game moving forward is something of an iteration of the Agricola-style worker placement design. Some have been insufferable (Le Havre, for example) and others reasonably interesting, but none have matched Agricola’s charm. Rosenberg’s newest, A Feast For Odin, makes a noble attempt but a few logical disconnects and a sense of too much of a muchness. If you like games with a lot of pieces, take note- this one has 16 punchboards’ worth.

Finally, a game with everything.

This is a worker placement game where you have over 60 possible choices as to where to put your worker. It’s a sort of “Viking sim†in a sense and not unlike a Phil Eklund game it tries to cram everything about that notion into one game. So you’ll send guys out into the woods to hunt or chop wood, you’ll build three different kinds of ships, maybe do a little whaling on the side, fire up the forges if the fancy strikes you, sail to distant lands to establish settlements and at the end of the day you’ll set up a meal of beans, salted meat, fish and other Northern European delights. That’s why it’s called A Feast for Odin, after all. Like Agricola and its heirs, it is also a resource conversion game at heart, where the idea is to make things and then work out ways to make things more efficiently, after which you make those things turn into other things. Also like Agricola, an occupation system imparts bonuses and strategic direction based on which ones you start with and acquire throughout the game. This sort of reigns in the broad range of options and provide some much-needed focus, and exploiting these advantages is key to winning the game.

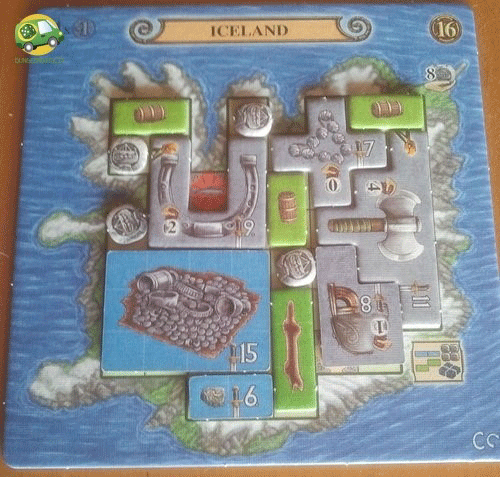

This is where part of my issue with A Feast for Odin ultimately lies. One of the key concepts of the game is transforming goods into luxury goods. So the red and orange goods, which represent consumables and daily products, need to get transmogrified by whatever means into fancy blue and green goods more indicative of your peoples’ success as Vikings. These are placed on a spreadsheet-like grid with a couple of tricky placement rules. The goods are different sizes, and the idea is that you fill up this spreadsheet from the bottom left up and as you go, your income increases and if you surround certain squares you produce a good automatically each turn corresponding to the enclosed icon. Now, at the top of this grid are -1 point spaces. So yes, as you might guess, the goal is to cover up all of these negative points. You can put down money on these spaces to fill them if you have to. There are also special, irregularly-shaped treasures that can be forged, purchased or pillaged. I have no idea why the Crown of England requires so much space to store, but there it is.

The Vikings measured their wealth by how many pieces they can fit on a spreadsheet. Later on, this would translate into excellent suitcase packing skills.

So this is very weird. You’ve got this very detailed, comprehensive look at Viking life. The game even includes an almanac that maps all of the game elements and concepts to historical facts, which is very cool and it shows the amount of thought put into illustrating the setting with these mechanics. But then, the whole thing is scored by this odd spatial puzzle that at times feels more like organizing inventory in Resident Evil than it does acquiring and measuring wealth. One thing I do like about this is how if you make buildings or decide to explore distant islands, you open up a new grid with MORE -1 point spaces. So there is a risk in expansion if you cannot produce or procure goods for these spaces. I like the sense of investment and trying to break even. And it is a pretty challenging game, although absolutely none of the challenge comes from what other players are doing. Sadly, unlike Bohnanza, this game is a completely solitary affair that exhibits the worst of the “multiplayer solitaire†failings. Turns can drag on with so many options available as players flip over calculations in their minds or try to work out the best way to place goods on those stupid grids. The solo game is pretty good as a puzzle to optimize your score and with two it can be pleasant, but I’d hesitate to sit down for the game with three or four.

This game is very much like a Radiohead album for me. I admire it and respect it more than I enjoy it. There’s no doubt this is a highly refined, studied and metered design. It’s broad and thorough, and it is clearly designed by someone that appreciates depth, variety and open play. But it also seems to lack the whimsical humanity of Agricola, where it was often satisfying just to make it through another turn or to get everybody fed for another season. The titular feast of the game is a similar kind of reckoning, but in it it’s another sort of spatial puzzle where you try to line up foods and meet the demand. Fail and you get a negative point token. But it never seems like the stakes or high, or that the players are as invested in it.

Regardless, I think fans of Caverna, Fields of Arle and so forth are likely going to be spending the next couple of months digging into A Feast for Odin, and I think for that crowd this game will likely be a crowd-pleaser. But I wouldn’t be surprised to hear some of these folks feeling a bit fatigued or even disappointed that this year’s model isn’t particularly striking off in a new direction.

Customer Support

Customer Support  Subscribe

Subscribe

Account

Account  Wishlist

Wishlist